And the year is 1934.

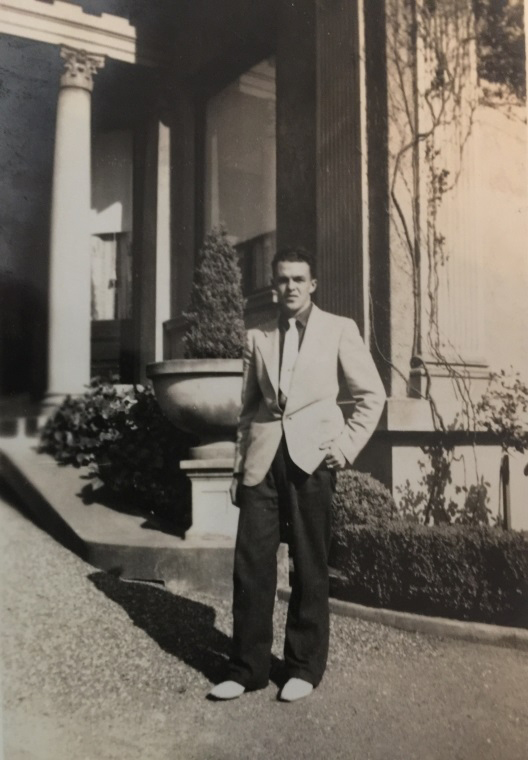

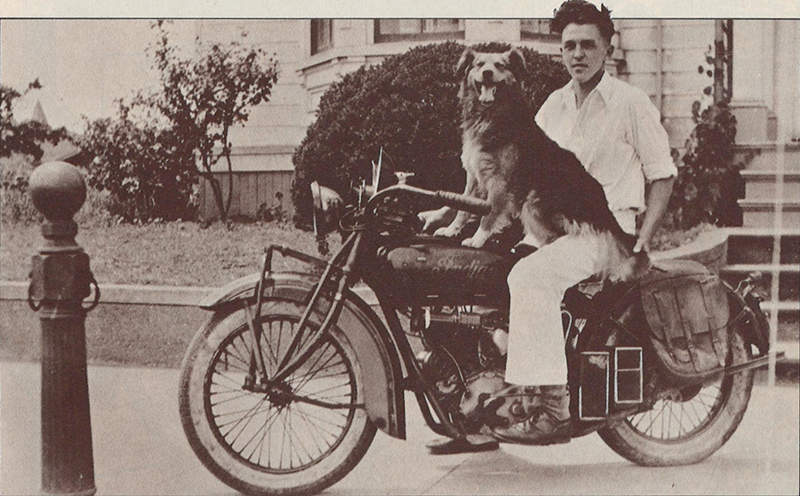

“Aviator!” a patron of the cantina shouted as people rushed out to see the aerodynamic Indian motorcycle that stopped in their small Mexican town. Humboldt B. Gates looked more like the aviator Charles Lindbergh that day than a motorcyclist with his pilot’s goggles, white silk scarf and leather flight jacket. A few weeks before, Humboldt had left his hometown of Eureka, California. It was the spring of 1934. He rode over 300 miles south through the redwoods, the mountains and inland valleys of recently completed Highway 101 to San Francisco. The Golden Gate Bridge was under construction but not yet open. It was a trip of dreams. He’d imagined Mexico City and was now on his way there. Humboldt had completed the modifications of his Indian motorcycle, gathered his tools, his clothes, a bedroll and the money he’d made working as a warehouseman and the airport, packed up his Streamliner and headed south.

After a week in San Francisco, Humboldt rode east on Highway 40 toward Reno, Nevada. As Humboldt’s Streamliner climbed the Sierra grade on Highway 40, a late spring storm descended. Temperatures dropped. Humboldt found himself moving through falling snow, on an icy road. Determined to make it to Reno, he bought a length of small rope and wrapped a piece around each wheel, alternately passing it through the spokes and over the tire. The makeshift chains caused a slow, bumpy ride, but he made it over the pass and into Reno where he was greeted by his uncle, U.S. Senator Key Pittman. He’d traveled with his uncle to Washington DC when he was younger.

After a few days in Reno with his uncle Key, Humboldt was ready for a warmer climate. He had his sights set on Mexico City. Before leaving Reno, Humboldt bought two extra tires, installed a luggage rack, and tied on a bulky five-gallon gas canister, which he would soon discard. The American highways offered a fairly smooth ride, and the weather turned favorable for a memorable and uneventful ride through the American Southwest—Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. With the southwest winds in his face, Humboldt could reflect back over the last 18 months and all the late nights in the shop building the Streamliner.

***

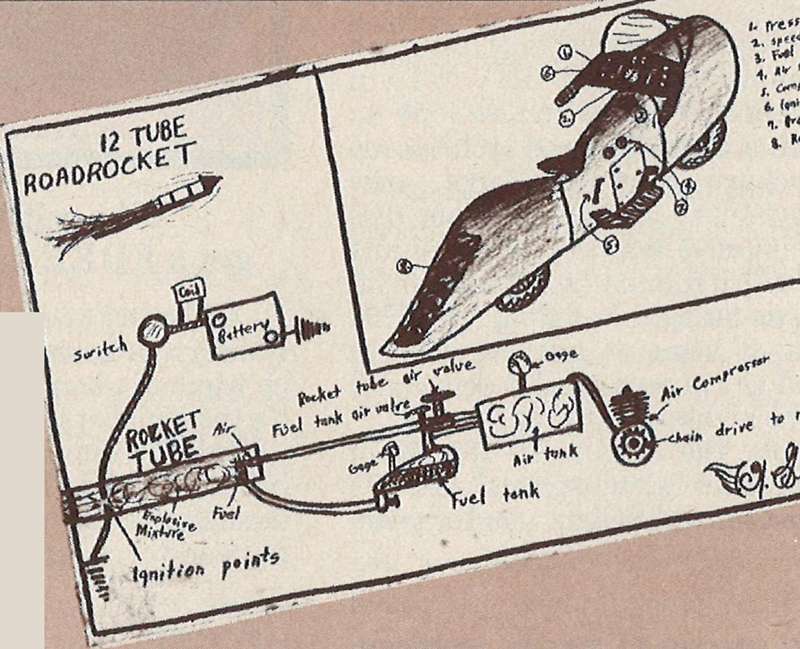

Humboldt started the metamorphosis of turning a stock Indian motorcycle into his own design – the Streamliner. He started the project in early 1933 in his mother’s converted horse barn at the corner of 8th and I Street in Eureka. He was 20 years old when he set out to revolutionize the concept of motorcycling. From his drag racing escapades, street racing and his job at the Eureka Airport, Humboldt got the inspiration to modify his Indian motorcycle into a machine of the future: a rocket-assisted streamliner. He envisioned a completely streamlined motorcycle body with 12 rocket tubes mounted in the tail section for added thrust. The locals never doubted Humboldt’s sincerity; they just thought he was a little crazy. So began the Road Rocket Streamliner project.

Humboldt had already owned a Harley-Davidson motorcycle, an Indian Scout and an Indian Chief before starting his project. He’d raced one-cylinder English Rudges on a dirt-track and was known locally as daredevil rider for some of the stunts he’d pulled off, including outrunning the police a couple times.

He landed a service job at the Eureka Municipal Airport with the idea of trading his wages for flying lessons, but he started seeing the possibility of combining airplane and auto parts with a motorcycle to achieve better aerodynamics. He soon forgot flying lessons and concentrated on the Streamliner.

The 12 tube rocket propulsion design he’d figured out had problems right from the start. Humboldt chose a fairly light bike to base his design on. He sold the cumbersome four-cylinder Indian Chief he’d been riding and channeled his resources into a smaller Indian Scout he’d owned since he was 16. Influenced by the aerodynamic lines of the air planes he worked around at the airport, Humboldt modified an old pair of Chrysler fenders to mount over the front and rear wheels of the Scout; then he secured sheet metal panels to each side of the fenders as full-length skirting. In addition, he covered both sides of the engine area with vented sheet metal which wrapped around and served as wind and gravel protectors for his legs.

For a windscreen Humboldt located a discarded fly screen from a biplane—including an air-speed indicator system. Few motorcycles in those days had speedometers. The windshield adapted to the Indian easily, but the air-speed indicator had a problem— it was accurate only on windless days. When the Indian rode into the wind, the gauge registered the bike’s speed plus the wind velocity. When the Indian rode with the wind, it read bike speed minus wind speed.

Once the machine was streamlined, Humboldt prepared to test his plans for the proposed rocket system. Rocket propulsion was not a new idea; the Chinese had been using it since the Thirteenth Century. But in 1933, in Eureka, California, nobody was experimenting with rocketry, except Humboldt. For his test site, he chose his mother’s backyard.

To prepare his prototype “rocket,” he capped one end of a two-foot-long, four-inch-in-diameter steel pipe and packed it with black powder mixed with dirt to lessen its explosiveness. This was essentially a pipe bomb. But he was trying to be conservative. An earlier design called for an air compressor and pressure tank to inject fuel into the tubes, and another idea was to test all 12 rocket tubes at once. The ignition system for this concoction was a single switch with a battery on one side and a coil on the other, leading to a set of points in the steel tube. With the tube secured to a fence post and his mother away from home, Humboldt threw the switch and ducked behind the garage.

The powder ignited with a concussion blast sent debris flying, damaging the fence and breaking two windows in the house. Neighbors came running. The “Road Rocket” part of Humboldt’s experiment was officially over. The neighbors were not amused. So he pursued increased horsepower by more conventional means.

With the services of a machine shop, he ported and relieved the engine, milled the heads and installed a different camshaft. He added air scoops and installed a small high-velocity air compressor, using it as an alcohol injector. The compressor, belt-driven from an additional pulley on the generator, communicated with the carburetor via an injector line; the alcohol, stored in a separate reservoir using a hand-pressure pump, was to be used sparingly. In Humboldt’s final mechanical alteration, he installed a lever-operated muffler bypass system.

Following the mechanical changes, Humboldt painted the Indian Streamliner a yellowish-beige and trimmed it bright red. It was ready for a road test, and he wasn’t disappointed. His modified Scout broke the 100-mile-per-hour barrier as he crouched behind the windscreen. For 1933 that was fast: the California Highway Patrol’s Chrysler Airflows topped out at 90 miles per hour.

Humboldt’s Streamliner became a point of local interest—especially with the police and CHP, whom he left in the dust on a few occasions. After one episode, when the police couldn’t catch him, they just waited for him at home and impounded the bike when he arrived. Humboldt’s mother worked at the court house and was embarrassed by the ordeal. A good humored judge sentenced the Streamliner to three months in the city jail, chained to a pole.

***

Everywhere, the futuristic looking Streamliner attracted attention. Even at the border crossing, Ciudad-Juarez, the Federales were more interested in the flashy machine than in where Humboldt was going or why. After thoroughly checking out, the Indian and all its gadgets, the border officials waved him through.

In 1934 much of the route through Central Mexico was unpaved. Burros, horses, sheep and cattle freely grazed along the roadside and could stray in front of vehicles. Mexican drivers didn’t adhere to speed limits much, yielded no right of ways and rarely used headlights. Humboldt parked his bike at night and only rode during daylight hours.

Humboldt adapted to Mexico in other ways. Unsure of the quality of Mexican fuel, he employed a trick he’d learned servicing planes back at home. From his first fuel stop south of the border in Chihuahua until he was back in the States, he filtered all his gasoline through a chamois cloth. Besides catching any unwanted particles, the chamois also absorbed traces of water. With a cruising range of 150 miles, however, the Streamliner was limited. Twice it ran empty between stations, and twice Humboldt was spared a long walk by passing motorists who provided extra gasoline.

From Chihuahua, Humboldt headed south toward Mexico City, which he reached three weeks after leaving Reno. Traveling only 35 to 40 mph because of poor road conditions, he had endured a long and dusty journey. Mexico City offered all the excitement Humboldt craved. His first day there, as he was cruising along the busy and unfamiliar city streets, a motorcycle cop on a vintage Harley Davidson—siren blaring—overtook Humboldt and motioned him to the side of the road. Figuring Mexico was no place to play hide-and-seek from the law, Humboldt complied, though he had no clue what law he’d broken.

After examining the Indian top to bottom, the burly and seemingly friendly policeman spoke to Humboldt in his native Spanish. Humboldt had no idea what he was saying since he didn’t speak Spanish. After a few minutes, the officer indicated that Humboldt needed to follow him somewhere. Humboldt was concerned. He nervously followed the officer through a maze of back streets. He considered just gunning the Streamliner and trying to lose the Mexican motorcycle cop. But this was Mexico City. He had no idea where he was going.

The policeman pulled over at a small diner where several more Harley-Davidsons wearing the insignia of the Mexico City Police Department were parked. As they pulled up to the neighborhood diner, a group of policeman emerged from the cafe. One spoke English. It turned out that Humboldt hadn’t broken any laws at all—the first officer simply wanted his friends to see this extraordinary machine. He thought they’d never believe a mere description. The officers poured over the Streamliner with the English speaking motorcycle cop translating questions and answers. Then they treated Humboldt to lunch.

Humboldt had another week in Mexico City before the 2500-mile journey back to Eureka. During that week he tuned the Streamliner and mounted the spare tires. Finally, he was ready to retrace his path. While on the road between Mexico City and the U.S. border, the Indian’s clutch failed. Humboldt limped into a local garage, where the mechanic assured him the nearest Indian parts were across the border in El Paso, Texas another 500 miles north. It looked as if his trip had ground to a halt.

Humboldt and the Mexican mechanic, who spoke broken English, put their heads together. Having disassembled the wet clutch, they discovered the fiber discs were ruined. They began poking through a junk pile behind the shop and uncovered a stack of steel paint can lids, close in diameter to the clutch plates. The mechanic used a metal punch to knock out the center holes for the shaft, and they reassembled the clutch. Humboldt fired up the Streamliner, released the clutch and it worked. Following toasts at the local cantina to friendship, success and ingenuity, Humboldt and the Streamliner once again headed north toward El Paso and the return trip to Eureka, California.

The following year, in 1935, Humboldt once again rode the Streamliner to San Francisco, this time trading it to a man for a Graham automobile. That was the last time Humboldt ever saw the Streamliner.