Falk’s Claim

The Life and Death of a Redwood Lumber Town

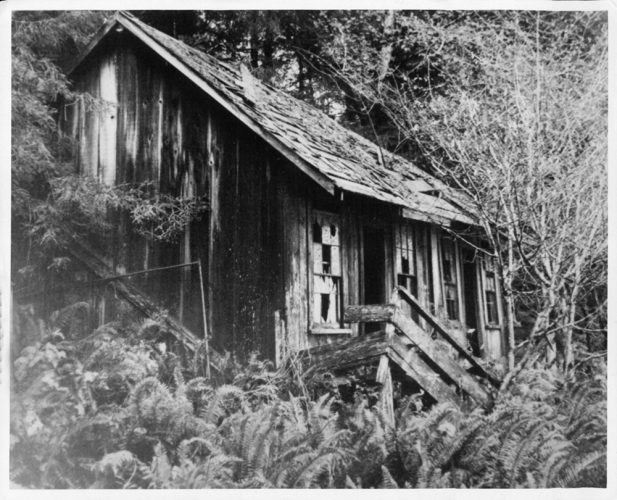

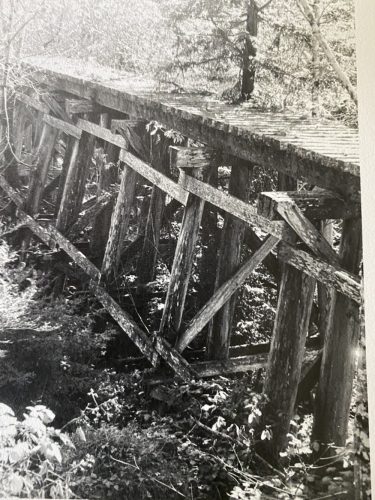

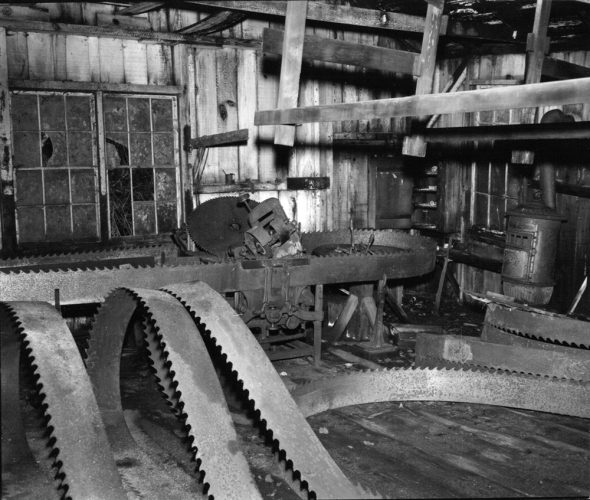

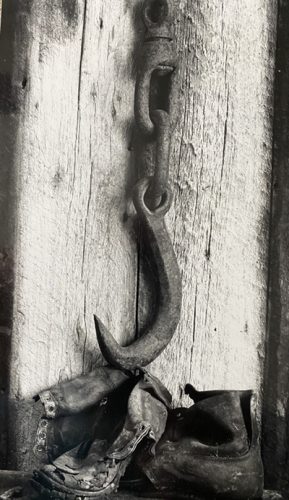

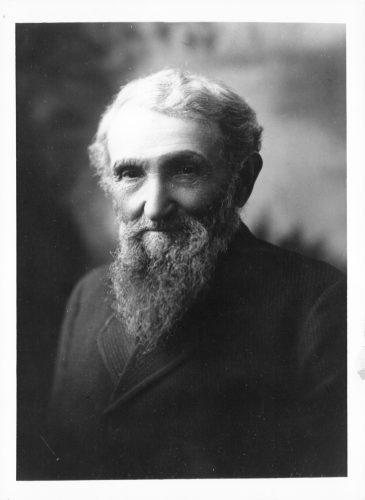

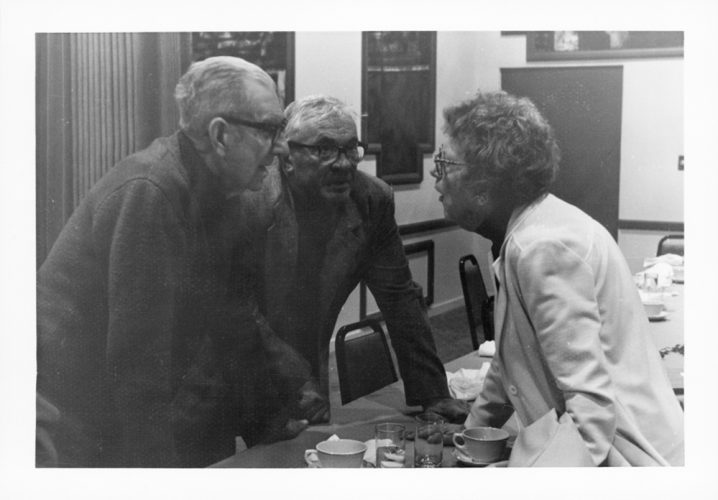

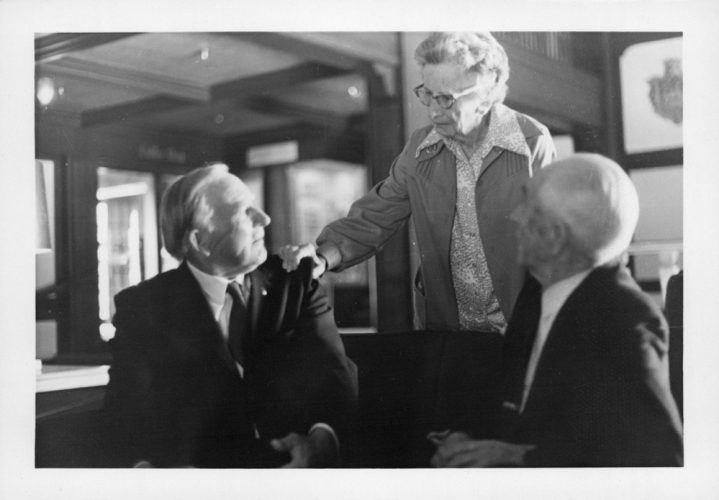

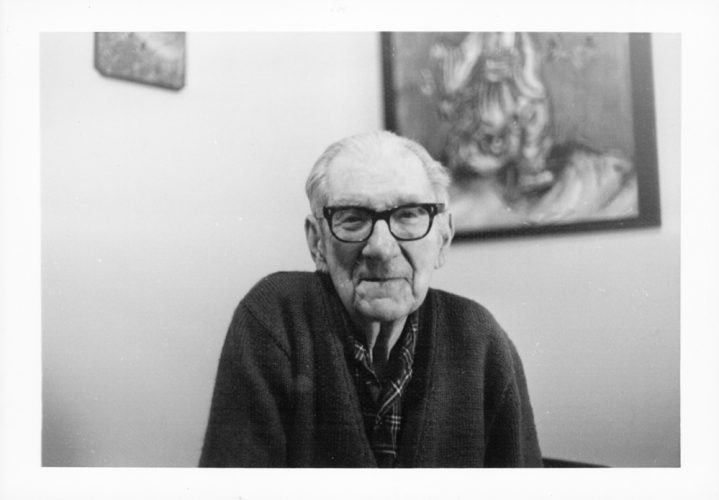

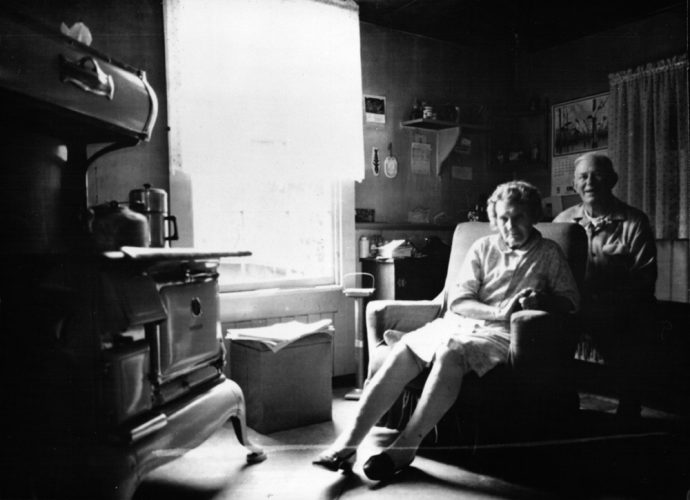

Nominated for the Forest History Award, Falk’s Claim chronicles a California north coast redwood lumber community from it’s bustling early days in the 1890’s though it’s decline to a ghost town in the 1950s. Told through personal histories, it is a vivid portrait of a disappearing way of life in small rural communities. Richly illustrated with more than 60 black and white photographs, the daily lives emerge – trusted neighbors, the rough-edged ways of the lumber camps, the town characters, the kids, the fights and the festivities. The author discovered the abandoned ghost town in 1968 while hiking in the Elk River Valley and became fascinated with the scores of vacant structures, including trestles, the mill, shops, the general store, cook house, homes, tools, wood stoves, vehicles and other memorabilia of the times. The author spent 10 years interviewing people who’d lived in the town, collecting photographs and reconstructing the history of the Falk ghost town. Throughout this tale, the sense of change and renewal challenge our notions of permanence, reminding us that our history is but a moment when measured against the enduring cycles of nature.

Falk through the ages

Photos by Sy Beattie, Jon Gates, Beverly Hanley, Teresa Porter

Excerpt

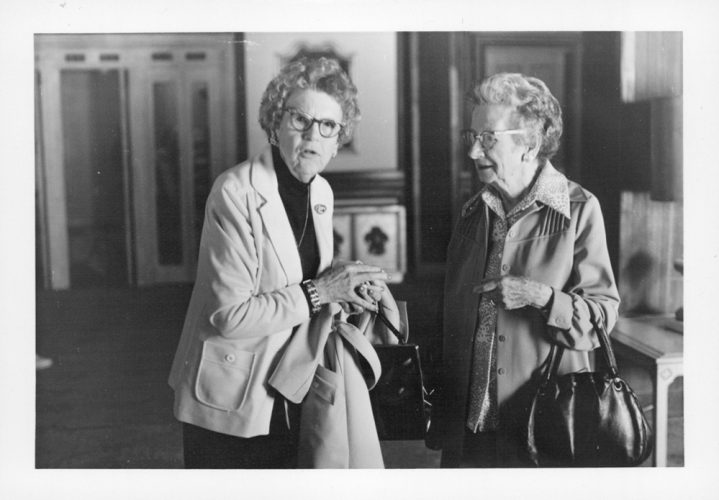

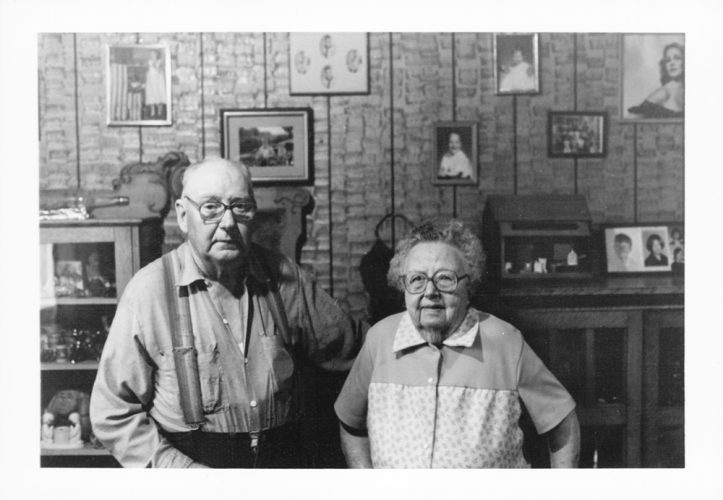

The Townswomen

The logging and mill work was a man’s world, and for that reason little opportunity existed in Falk for women to acquire a profession. The only jobs available for women in the town were kitchen work in one of the cookhouses, or, if they were qualified, teaching at the Jones Prairie School. For most women, the choice was between moving to the city to learn a skill, as many of the young women did, or staying in the town to fulfill a more traditional role and raise a family. Those women who made the latter choice were vital to the community’s success. The work that was involved in maintaining a household rivaled that of the woodsman, and the reward was a homespun existence, from the clothes the family wore to the food they ate.

At a time when kitchen conveniences consisted of a wood cookstove and a sink, food preparation was a time-consuming chore. It meant maintaining a large garden, picking berries, baking bread, cooking with whole grains, stocking a root cellar, and taking on huge annual canning projects that put fruits, vegetables, fish and meat on the storage shelves for the coming year. Some of these families had six or seven people in the household, so a substantial amount of food needed to be processed. Of course, a family of that size also produced many extra hands to help with the chores.

Along with the food preparation there was also a mountain of dirty clothes, all of which were washed by hand, and a continual need for mending and sewing which, if one were fortunate, could be stitched on a treadle sewing machine. Also at hand were a multitude of other tasks; making soap and candles, chopping firewood, taking care of the chickens and maybe a cow or a pig. The work at home was a continuous process, just as the logging was for the woodsmen, and like the woodsmen, the women had a certain peril to face—childbirth.

Living in a town that lacked a resident doctor created a great inconvenience for those that needed immediate attention. Realizing this, Dr. Curtis Falk, Elijah’s son, tried to offer his services to the people in the town. With only a moment’s notice, Curtis often rode out to Falk in his horse and buggy to tend an illness or injury which had occurred. Some of these were emergencies, however, and could not wait for a doctor to be summoned to the town.

On one occasion a pregnant woman, Mrs. Ida Fleckenstein, rushed into the company office and shocked Vernon Olson when she exclaimed that she was about to have her baby. Vernon knew a little first aid, but he was not about to volunteer his assistance in childbirth. He commandeered the only vehicle in town, and setting the world’s speed record over a corduroy road, raced Ida toward Eureka. Vernon became nearly as desperate as his laboring passenger, but managed to reach the hospital just as the birth was about to occur. This obviously was not the standard procedure for every birth in the community, but it was an example of the vulnerability a woman faced at her crucial hour.

Most of the women who lived in Falk were content with rural life and the rewards it offered. But one young lady from Falk, Grace Rushing, followed her heart’s desire to become an opera singer. Her path to recognition was a cinderella story, except that she possessed a silver-lined voice in place of a glass slipper.

The daughter of Evan and Louisa Rushing, Grace grew up in Falk, where her father worked as a zoogler. She shared the family household with three sisters and three brothers, and though they were quite poor, their father made sure they had a comfortable home, food to eat, and clothes to wear. At 18 years of age, Grace realized her future was not in the Elk River Valley, and she moved to San Francisco to take a job. In her free time she began to train her voice for opera and studied under several accomplished instructors. While living in San Francisco, Grace was married, and she adopted her married name on stage, calling herself “Madame Henkell.” She spent several years in New York City, performing for large audiences, and toured the country, before settling down in San Francisco, where she sang in the City Opera. But Grace never forgot her roots in Humboldt County and returned for a public appearance at the Rialto Theater in downtown Eureka.

The path that led Grace Rushing out of the Elk River Valley was not a path every woman could, or would want to, travel, because it meant leaving behind family and friends, and all the benefits of a close community. On the other hand, an independent-minded woman who wanted a job outside the home found it difficult to live in such a small town. There was one exception to this general rule, Maggie Biord, who ran the logging camp cookhouse. Maggie became one of the only women to develop a successful career in the company town, bridging the gap between the role of the working man and the role of the working woman.

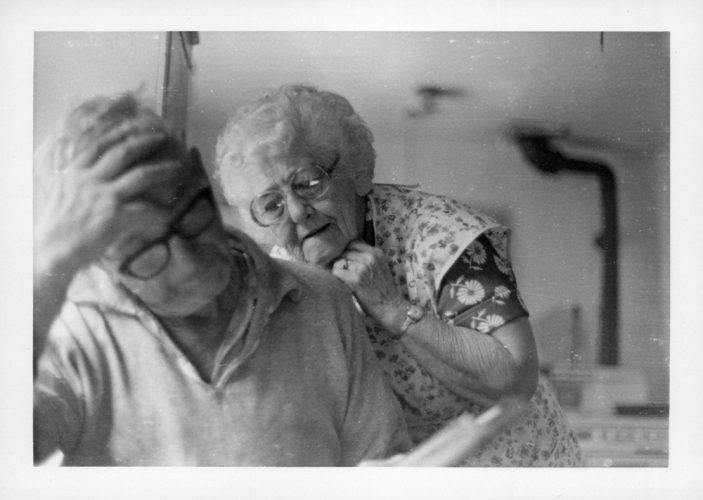

Maggie

Maggie’s personality was colorful and outspoken, and she had an intense desire to offer the best food service possible. Her vitality was unique, and her energetic enthusiasm created a spirited life around the camp. Part of this spirit was a volatile temper. No one dared cross Maggie. Even the company bosses took their hats off when they entered the upper cookhouse. In fact, Falk’s main logging camp was known as “Camp Maggie.” She was a married woman who really did not have to work, but she loved to cook. Although she left the camp several times, she always returned to the job, and over the years, built up quite a reputation in the town. Physically, she was a big woman, weighing over 200 pounds and endowed with a loud, booming voice. Maggie was a hard worker and expected everyone around her to be of the same fortitude when it came to getting the job done. Her kitchen crew prepared three meals a day for 100 men with robust appetites, so the preparations and cleanup were immense and continuous.

Maggie knew the type of meals men liked, and served them to the workers in huge portions. Her philosophy was that if a man left the table while there was still food on it, then he knew he’d had enough. On the breakfast table every morning were steaks, eggs, potatoes, donuts, pancakes, oatmeal, and coffee. The two 60-foot tables used for dining sagged visibly when loaded with the enormous weight of food and dishes. In a matter of 20 minutes, after “seconds” and “thirds,” the dining hall emptied and the kitchen crew once again began the cleanup.

Her fiery reputation traveled further than the town, and sometimes it was difficult to locate people that were not afraid to work for her. She had very definite ideas about how a cookhouse should be run. Bus carts were not used to move the dishes and food because she felt they made people lazy; instead, everything was carried by hand. The plates weighed two pounds each, and the cups were thick, heavy and round, with no handles, so it took a lot of hustle to move what amounted to nearly three quarters ofa ton of table settings per day, not including the food!

Thursday evening was the big dinner feed of the week. Maggie served steaks, chicken, fresh fruits and vegetables, two or three different kinds of pies, several assorted cakes—everything a hungry working man might dream about. She made all of her own bread and pastry, and sometimes cooked 40 or 50 pies at one time. The cookhouse received four sides of beef each week, and along with her normal cooking duties, Maggie completely trimmed and cut all of this meat herself. If any of the food was not top quality, it was returned or discarded.

Always in good humor, Maggie maintained a friendly quarrel with Matt Carter, the general store manager. He provided the supplies for the upper camp, and at one point he thought Maggie was serving too much food and cut back on her order. When the Gypsy arrived at the upper camp with fewer provisions than she had requested, Maggie laid into the superintendent who had delivered the order and told him that she was “gonna come down and whip Matt Carter if that damned order wasn’t filled.” That afternoon the Gypsy showed up again carrying the balance of the groceries. Matt had not known what to think of Maggie at first, but he learned that as long as she received what she requested there would be no problems—provided the goods were fresh. Once, he sent some rancid butter up to her, and she immediately phoned the store and screamed, “Matt, you’d better get out on those tracks ’cause that butter you sent up here was so damn rotten it just started walkin’ back down the hill.”

These outbursts were typical for Maggie. Her temper was short, and she made no pretense about it. But she was not entirely brimstone and fire; she had a personable side about her too. She cared for the people that worked for her, and if they passed her test of hard labor and dedication, they soon saw beyond her gruffness, and experienced a woman with a big heart.

Maggie separated from her first husband and continued to cook at the camp while raising her five-year-old son, James. She was joined in the kitchen by her sister, Suzi Glass, and the two of them worked together and helped to create a social life in the logging camp by hosting occasional card parties. Those were enjoyable get-togethers and the two sisters always concocted special dishes to enhance the evening’s entertainment. But darkness entered Maggie’s life when her son James was killed by an accidental gunshot wound just before his sixth birthday. Though burdened by this sadness, she was not one to complain of her misfortunes. Several years later she remarried and became Maggie McNeill, but up at the cookhouse she was always known as just plain Maggie.

One of the few times Maggie was ever embarrassed by her own antics was after an incident which occurred during her last reigning years at Falk. A friend of Noah’s who had invested money in the company came to Falk to inspect the operations. During the course of his tour he happened to pass through Maggie’s kitchen and the aromas caused him to lift a lid from one of the cooking pots. Seeing this nosey stranger at her stove, Maggie picked up a meat cleaver of considerable size and began running and swinging toward the man, yelling, “I don’t allow no son-ofa-bitch to take the lids off my pots.” After discovering the identity of the “son-of-a-bitch,” Maggie felt a twinge of nervous embarrassment in the presence of the company’s new investor. The incident was forgivable, however, because as everyone knew, that was Maggie.

One year, Maggie decided to take a leave of absence from her kitchen duties at the camp cookhouse, and the company was forced to hire a new cook. Whoever was to replace Maggie had a tough act to follow. A fellow by the name of Bowman was the first to try. His cooking was sloppy, though, and the food was greasy and tasted terrible. Serving bad food in a logging camp was as obvious as pumping water at the local gas station. After two weeks of this, the men began to grumble among themselves, but decided to give the new cook more time before confronting him with the issue. A week passed without any complaints, but the food did not improve. Finally something had to be done.

Peter Oberdorf was working in the blacksmith’s shop and had stepped outside for a breather when he saw the woods crew walking down the tracks towards camp. Woods Boss Jim Copeland stood on the blacksmith’s landing nearby and was nervously rolling the brim of his hat, which was a sign of trouble. “The goddam men want to run the ranch. Well, they can go ahead, I’m through,” he said to Peter. “They’re on strike for a new cook!” Copeland was upset because he had known nothing about the strike talk and, in the company’s opinion as well as his own, he was supposed to be in close communication with the men.

The crew entered the cookhouse and two of the hook tenders negotiated for the strikers. It wasn’t long before Winfield Wrigley arrived from town aboard the Gypsy. His mood was solemn but his message was clear. He flatly stated that those who did not return to work immediately were to come down to the office, collect their pay, and seek a job elsewhere. Winfield did not enjoy this position of enforcement, but as the acting company manager he had to take control. His position was somewhat strengthened when Jim Copeland stepped forward and gave his word that he would hire a new cook within a week. Satisfied that their demand had been met, the crew headed back to the woods.

The cook and his assistants had felt the pressure mounting and were ill at ease during the entire confrontation. When Jim Copeland told them that he was going to hire a new cook they became very angry. That afternoon the kitchen crew threw all the cookhouse food out the back door and down the hillside—meat, bread, milk, flour, everything, and departed on the next log train to town.

The company managed to quickly locate a replacement cook but his first day was difficult. He and his helpers had to scour the brush on the hillside for the discarded food in order to salvage the evening’s meal. Things worked out better with the new kitchen recruits. The woods crew was satisfied and realized that not everyone could serve a meal like Maggie could. But with Bowman as a greasy reminder, they knew it could be a lot worse. The food strike was the only strike ever to occur at Falk.