Navigating a 7,000’ Decent from Mt. Shasta’s Summit

Sixty and seventy knot gusts of wind swept the face of Mt. Shasta in the night. Our tents were anchored 2,000 feet above treeline, lashed to sunken ice axes and chunks of lava jutting from frozen snow. I hadn’t slept much. At 4:00 am, I lay in my down sleeping bag with the tent door open, watching the full moon silently traverse the southern sky. Surges of wind battered the thin nylon structure. Hours before, a big gust had picked up one of our dome tents and flung it 200 feet down the mountain, spilling boots, packs and sleeping bags out onto the snow.

Anxiety kept my nerves and imagination locked onto Mt. Shasta’s 14,180 foot peak. Nearly every spring for the last 12 years, I’d climbed and skied different snow faces and chutes on the south side and the north side of the massive mountain. But I’d never skied off the summit before. I thought about Red Banks. The chutes above Red Banks were steep and they ended at a cliff drop into Avalanche Gulch. No room for error there.

Outside the tent, voices rose over a sputtering, high altitude cook stove. Flashlight beams pierced the darkness as climbers in our group got ready. We’d started our climb the day before from around 7,000 feet elevation. Our summit trek would take us up Green Butte Ridge under moon light, and up into Avalanche Gulch by sunrise.

Frozen snow crunched beneath heavy climbing boots as seven us set out in single file across the moonlit snowfield. Each breath turned to an icy wisp, disappearing in the wind. The entire mountain seemed luminescent, every ridge line and snow surface visible against black sky. Several in the group had never climbed on ice before. The lead climber had been mountaineering for over 20 years. The previous day he’d made sure everybody could execute an ice ax arrest.

The snow hadn’t iced over at lower elevations, so we hiked without crampons. When we dropped into Avalanche Gulch, the winds subsided slightly and the eastern sky lightened to a smokey silver. Each climber carried a day pack with an ice axe. I was the only one with downhill skis, boots and poles strapped on my pack.

Avalanche Gulch steepened as we reached 10,800 feet. We kicked footings into the snow and climbed slowly. Our party began to string out over a hundred yards, seven tiny specs on the mountain. I stopped to catch my breath. An enormous mound of crumpled ice and old snow lay frozen in the middle of the canyon. I looked up to Casaval Ridge, two thousand feet above me and remembered when Shasta didn’t seem so safe.

On a previous Shasta climb, a tropical storm had produced greenhouse like temperatures and the snow hadn’t frozen that night. Not even in the higher altitudes. Muffled rumblings of avalanches interrupted our sleep in the night. We decided to climb anyway, which wasn’t a good idea. I carried my downhill ski gear, hoping to make it to the summit or at least Thumb Rock at 12, 923 feet. The air was uncharacteristically still and sultry. Three of us had paused for a rest in upper Avalanche Gulch; five more climbers from our group were scattered along the snow canyon within a hundred yards of us. Below them a dozen climbers from Oregon moved a snail’s pace. We’d passed them on the ascent. They looked like a colorful little caterpillar in their tight formation with red, blue and orange snow parkas.

Seconds later, the avalanche broke loose above us.

An enormous ice wall, suspended over three snow chutes at the very top of the canyon, toppled silently off the ridge. For a couple seconds we didn’t say anything. It was surreal. It seemed so remote. Then it grew, fanning out dramatically. The three of us shouted warnings into the canyon below us as we scrambled out of the path of the expanding avalanche. The tiny dots below us scampered for safety too.

A twelve foot high breaker of ice and snow rumbled down the mountain. Blocks of ice the size of automobiles tumbled end over end. The snow pack shook as though the whole slope might let go.

We lost sight of the climbers below us momentarily. A river of slush hissed for 10 minutes in the wake of the avalanche. We moved down slope to regroup; everyone was okay. The Oregon climbers weren’t so lucky. Their leader suffered a cardiac arrest. They placed him in a sleeping bag and attempted to revive him. The mountain would be his final memory.

At 11,300 feet, the snow surface hardened to ice. Crampons were needed, so we closed ranks to strap the steel framed climbing spikes onto our boots. Above us, Red Banks gave the illusion of a summit. The fall line rose sharply. I pounded in my ice axe into the hardpack and straddled the thin metal shaft so I wouldn’t slip while attaching the crampons on the steep pitch.

I kept glancing up at Red Banks, watching for any sign of falling rock. Rockfalls were more of a threat than avalanches. It was still early in the morning. But once the snow started melting, the rocks would roll. The unofficial rule of safety on Shasta was to be off the high mountain faces by noontime in spring and summer.

We began climbing again as the first rays of sun broke over Sargent’s Ridge; Thumb Rock stuck out like a castle turret from the rock outcroppings. We were on the Heart, a steep frozen snow slope that rose 1500 vertical feet in less than half a mile. We put on goggles. Tiny ice pellets blew at high speed down the slope, stinging our faces. The air thinned noticeably at this altitude. We’d climb 15-20 steps then pause, replenishing oxygen, planting our spiked axe handles into the snow pack. My lungs and throat ached.

Halfway up the Heart we stopped for water. A 40 knot wind blew down off the ridge, jerking at my skis and forcing me to crouch in close to the incline. Someone above me fumbled a plastic water bottle. It hit the icy slope like small missile, rocketing into Avalanche Gulch a thousand feet below. I tightened my grip over the head of the ice axe and jammed both crampons deeper into the Heart’s frozen surface. Mind games conjured a human torpedo in uncontrollable descent. Concentration became pointed; metal spikes, an axe tip and a volcanic peak. We moved on. Slowly.

The Heart seemed an endless staircase of ice. I felt dizzy. Thumb Rock welcomed us with its crow’s nest refuge, approaching the 13,000 foot mark. I pulled an apple out of my pack and looked back down the 2,000 foot face of frozen snow we’d just climbed. I hoped that by noon, the sun would loosen it. Otherwise, skiing down the iced double-fall-line surface would be brutal.

After resting, we shouldered our packs for the final slug to the summit. We walked single file along a narrow ridge. To our right, a snow cornice formed an ice lip over the rim of a stadium sized natural amphitheater that cradled Konwakitan Glacier. To the left, snow chutes descended between rock wall openings into the Heart. There still wasn’t a cloud in the sky. The ridge line widened and steepened as we climbed above Red Banks. We approached three more snow chutes, flanked by rock spires.

A headache tapped insistently as I adjusted to the altitude. I paused to study the chutes. They looked bigger up close than from the camp. Plenty of room to make turns. I could traverse back to middle ground at the bottom of the chutes. About 100 feet of open snow separated the lower chute openings from a sheer drop over Red Banks.

Misery Hill. The false summit. My headache throbbed. Maybe I was hiking too fast. After cresting the ridge I wanted to see the summit in sight, not football fields of snow sloping ever upward. We trudged along, fifteen steps at a time, weariness battling willpower. At the top of the snow fields, Shasta’s final summit crested into view – 14, 162 feet. The last 200 feet of rock spiked upward, shrouded in blocks of blue ice. The peak had seemed like an illusion with each successive snow field. I forgot about the headache.

The seven of us gathered on Northern California’s highest pinnacle. We gazed over an earthly panorama encompassing thousands of square miles in every direction; Oregon, Nevada, Lassen, the Trinity Alps, Sacramento Valley, and beyond, to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. The dry plateaus to the east near Alturas were painted in soft browns. Jagged volcanic ridges crept thousands of feet down into the forests, in every direction, like the tentacles of an enormous octopus. The sun felt warm in the shelter of the summit’s east side. The sky was such a deep blue that it appeared black against the white snow. Faint odors of sulphur steam swirled in the crisp air, reminding us that Shasta still lived and breathed with deep connections beneath the earth’s surface.

I walked down volcanic scree on the summit’s Northeast face. The natural trail ended at a jagged and crumbling rockfall, descending a few thousand feet down the Wintun Glacier. Heaven was tinged with paranoia. I remembered reading about earthquakes that rattled the double cone giant. A slight volcanic sneeze could send hundreds of tons of rock crashing down. It could cause shifting in the deep fissures of the northern glacier fields.

One season we’d climbed the north side of Shasta. That was a much more technical and risky approach. Our climbing leader was rigorous about all of us being roped together as we traversed the icefields, stepping around what seemed like bottomless crevasses that descended into infinite blue light. I was lowered 60 feet on a line into one ice crevice. I was mesmerized by the surrounding luminescent light that seemed transparent and translucent, with undulating organic shapes that just kept descending into the abyss of an ever deeper tone of blue. I could never see a bottom.

I had my skis with me on that climb as well, but didn’t attempt to take them to the summit. There was too much exposure, almost vertical blue ice and the crevasses below. When we summited on the Shasta’s north side, we were all roped together. The climbing leader chopped foot holds into the boiler plate ice wall. I felt like we were climbing up a ladder it was so steep. Two climbers were directly above me, two below. Ice screws secured our line in case we fell. I remember looking at the bottom of the next climber’s boots and crampons while he swung the axe chopping those foot slots. Concentration didn’t allow any room for fear. But I felt that after we’d summited and returned to camp. The image of being nailed onto that ice wall remained vivid.

During that four day climb on Shasta’s northern flanks, we were the only people there. It was silent with no winds. I did a couple morning hikes with my alpine gear up onto large snowfields and skied down some enormous untracked basins. Our base camp was set about 10,000 feet. But I stayed below the ice wall and glacial crevasses with my ski gear.

After an hour on Shasta’s summit, I locked into my ski bindings. My chest felt a little hollow. A case of high altitude nerves. I stood in place. Both ski poles planted in the ice, sliding the metal-edged skis back and forth to loosen my knees. Someone else would carry my ice axe and crampons. If I fell, those would be bad companions to tumble with. My friends stood in a small group and waved me off. Butterflies turned to bats. I pushed off across the summit plateau. The snow looked purple through the downhill racing goggles. Descent.

I let both skis run straight with the bases flat to gain speed. The wind grew louder. The skis hissed in their tracks, jolting sharply over small clumps of ice. My knees recoiled from the shocks; both feet tingled. Concentration and rhythm took over. The nerves disappeared.

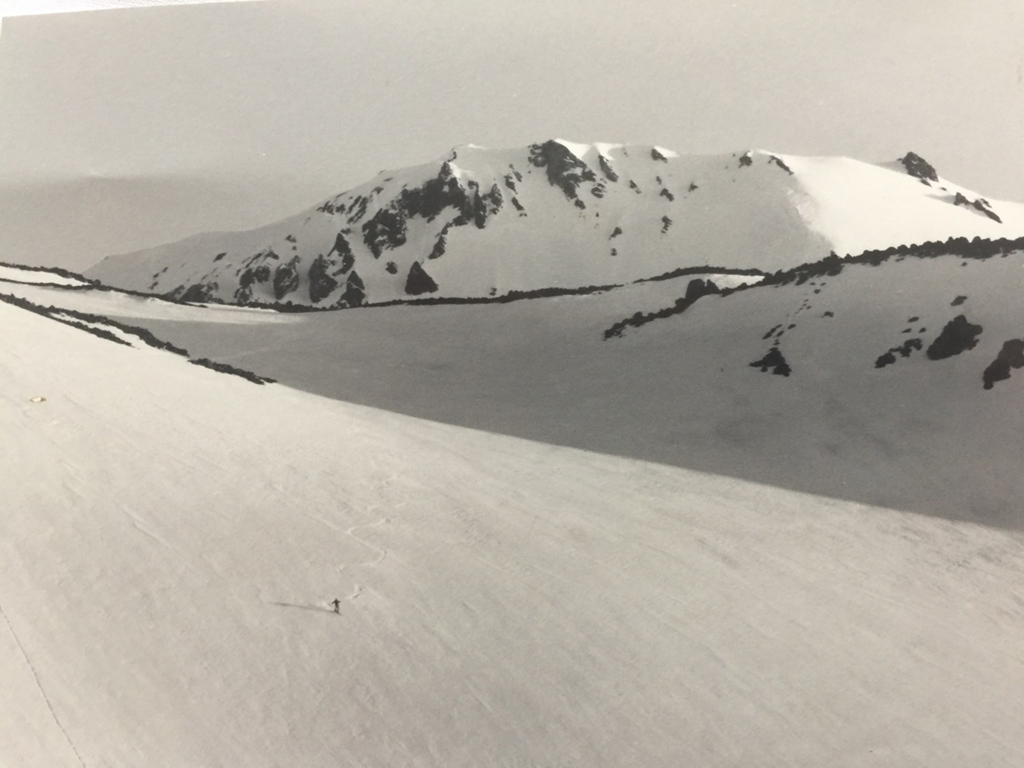

When I plunged over the top of Misery Hill, the world opened up beneath me. I made a quick stop, digging in the metal edges. Shasta’s south face dropped 7,000 vertical feet. A skier’s fantasy, without a lift line. The giant snowfield seemed suspended in the sky with no other mountains around it, just a sheer drop into the surrounding forest lands in every direction.

One last equipment check. I cranked down the metal boot buckles another notch and adjusted the goggles. My pulse quickened from excitement and thin air. I glided across the snowfield, accelerating. Sun had loosened the pack. It was perfect spring corn snow.

The skis started to run. Exhilaration rose with wind sound, skimming an ice pebbled surface at 40 miles per hour, taunting every reflex. Razor sharp edges responded instantly to carving. At high speed, the skis became momentarily airborne. Short hops over uneven snow surfaces. Arcing giant slalom turns gobbled up Misery Hill in a couple minutes.

Red Banks chutes came into view. I slashed a steep-angled radius to check my speed, picked a line, and dropped into the middle snow chute. The chute pitch dropped another 20 degrees. I felt it in my stomach. Don’t fall here. Red Banks below. Scattered lava formations blurred in my peripheral vision on both sides of the chute. Face, shoulders and hands straight down the fall line, wedeling with sharp slalom strokes.

The cute ended quickly. I pulled a hard left traverse, 30 yards above the Red Banks cliff into Avalanche Gulch. Skiing on the edge. Both thighs burned. My lungs pleaded for respite. Breath was short. Mountain air at 13,000 feet. Everything seemed quiet when I stopped. The snow had turned to corn sized pellets. No more ice.

I pushed off again. The skis chattered and squirreled over a chopped surface where scores of climbers had walked on their path to the summit. I traversed above the next snow chutes that opened into the Heart. The passage looked sloppy. Small red and black rocks littered the snow shafts.

Into the chute, a quick flash of edges cut the snow. No room for turns. I pointed both skis straight down the alley-way, looking for a place to land. Acceleration came instantly. The Heart was wide open. I skidded to a hard stop, happy to avoid snow snakes, cartwheels and face plants.

Red Banks chutes were narrow. Flying out into the Heart was like landing on a mountainous airstrip. I looked down the vacant and sprawling half mile long snow face – one of North America’s premier downhill runs. Rock walls stood distant. An uninhibited drop. The Hearts lower left face plummeted steeply out of sight, giving the illusion of a cliff. It also made for an interesting descent because it posed a double fall-line with the face descending steeply toward the south into Avalanche Gulch, while the left side of the Heart fell away at an even steeper angle towards the east.

Skiing the Heart was an endless dance. Swaying knees, rhythmic hands held high, floating down a massive snow covered surface, almost free falling on the steepest pitches. Riding a thin metal edge along the earth’s gravity. I don’t remember how many turns. Maybe a hundred. It didn’t matter. I found the zone. I was locked in it and everything seemed in balance. The purity of those moments vanquished any thoughts or doubts about anything in the world. Living in the moment. Several minutes of dream time to sweep a snow face that took nearly two agonizing hours to ascend.

The drop down into sunbaked Avalanche Gulch – 1500 vertical feet below – proved anticlimactic. Direct sun rays had turned the massive lower snow basin into a sea of heavy wet, slushy type cement. I skied 100 foot giant slalom traverse arcs to grit my way back to base camp. I reached camp quite some time before the others, who glissaded down on ensolite pads. From camp it had been a grinding six hour trek to the summit. The return trip took about 20 liquid minutes on skis. I lay there in the sun at camp and looked up at the volcanic peak more than a mile above me. Only minutes before, I’d been a tiny, fast-moving speck floating down the Heart of Shasta.