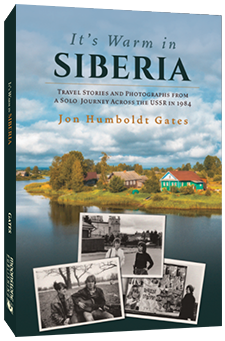

It’s Warm in Siberia

Travel Stories and Photographs from a Solo Journey Across the USSR in 1984

In 1984, Jon Humboldt Gates, having spent two years studying Russian and planning his journey, left his rural home on the California north coast and landed on the shores of the Soviet Far East by ship via Japan. He spent the next eight weeks traveling by rail and automobile through Russia and Ukraine, riding the full length of the Trans-Siberian Railway, driving alone for hundreds of kilometers through Russia and traveling south to the Black Sea. Along the way, he met scores of people from all walks of life, most of whom had never met an American before; an old woman with six white geese on a country road who pleaded with him for peace, a 14-year-old boy from Siberia who shared his love for dogs, a man who invited him to plunge into the icy waters of Lake Baikal, a group of musicians in Kyiv (Kiev in 1984) who became the seed of a transnational music project, and an ice cream flavor Baskin-Robbins had never imagined. He formed deep friendships, some that were lasting, others that were celebrated in the moment.

First published in 1988, this second edition is being re-released in the midst of a great tragedy across the frontier of Russia and Ukraine. These events could never have been imagined in 1984. Many of the people in this travelogue are from Ukraine and Russia, and a few from other Soviet republics. No matter where they were from, people across the USSR in the waning days of the nation were universally hopeful for a better world, a peaceful future, and they enthusiastically welcomed a foreign traveler in their midst.

Excerpt

Along the Dneiper

I would never forget how I met Anatoly and Valentina in downtown Kiev that day in 1984. I’d just arrived in Kiev after a week at the Black Sea resort of Sochi, in southern Russia, and a few days in Odessa, in southern Ukraine. I was wandering around in central Kiev, a city of more than two million people. I’d been walking miles since sunrise, traversing the historic metropolitan center, strolling along the Dneiper River, crossing bridges, touring the Lavra’s underground tunnel of buried saints, standing at the edge of the historical Babi Yar Memorial, walking along pathways to the towering Motherland Statue, and eventually ending up at a bus plaza in the afternoon, looking for transportation to an outdoor architectural museum I’d read about.

The bus complex was large. Buses departed to outlying districts and other regions. I figured it was a long shot that a bus even went to the museum. I was tired. I studied the crowd, the Cyrillic signs, looking for a point of recognition, somebody to ask which bus to take. There were probably more than five hundred people in the plaza and dozens and dozens of buses, coming and going.

Across the plaza, I spotted a young couple, nicely dressed, who were standing by themselves, apparently waiting for something. They seemed approachable, so I walked over to them and asked if any buses went to the Outdoor Museum of Wooden Architecture, bumbling my pronunciation in the attempt.

They looked at me, absolutely surprised—not just because it was clear I was a foreigner but because they were waiting for the same bus to the same park. I was happily stunned and relieved.

Valentina invited me to accompany them and insisted on buying my ticket. The historical park was about twenty miles outside the city. We launched into a spirited conversation in Russian, trying to map out how this serendipitous moment had occurred. Anatoly smiled and engaged my limited command of Russian with a staccato of questions and humor. He would look at me directly at times, then his gaze seemed to wander from behind his smoke-tinted glasses, but he was warm and personable. I didn’t know until we were well out into the countryside that Anatoly was blind.

I spent the day with them, walking along paths that wound through forests and hills where more than two hundred wooden buildings stood, all resurrected from past centuries. Anatoly asked that I call him Tolik, a more diminutive, personal name, and his wife, Valya.

Later that evening, sitting around their kitchen table, Tolik’s fingers raced over the keys of his silver and black accordion. A wide smile played across his face, his head rolling easily, accenting every note, his right foot keeping rhythm. Everyone in the small apartment rode the crest of his melodic passages, listening to Georgian, Russian, Ukrainian, and Romani folk songs. Tolik’s soulful rendition of Midnight In Moscow left me feeling pensive.

The evening reminded me of parties at home—friends gathered around a big table, simple food, a few bottles of wine, and music. A succession of dinner parties with old friends had spawned the band I had played in for the last ten years. A couple of the guests in Tolik’s band had known each other since school days.

“It is best when bands and friends can be together over many years,” he said.

Tolik had not been blind all his life. When he was twenty years old, he been studying to be a painter, like his father, but he lost his sight abruptly one night in an auto accident, when he plunged through a windshield. Five operations and fifteen years later, he still lived without eyesight but retained a great reservoir of humor.

“Zhon! Zhon!” he said, sitting at the table that night, pushing a plate of chicken sandwiches toward me. “More sandwiches? Ha, ha. Tomorrow you will have feathers—puck, puck, puck…”

“Zhon! Don’t drink too much wine.” His animation stirred laughter among friends. “Boool, boool, boool, potom, xryou, xryou, xryou.” Glug, glug, glug, then, oink, oink, oink.

“Eta shootka.” That’s a joke, he’d say, after making any comical sound effects and comments.

I kept forgetting that he was blind and gestured with my hands to aid my conversation. Hand signals comprised an integral part of my Russian language ability.

I gave Tolik a cassette of our band. He put the tape in his player and turned up the stereo. He sat back, inclining his head toward the ceiling, and listened closely, refraining from conversation, absorbing the unfamiliar rhythms and vocals: Yankee rock, fused with reggae and African styles. He was enjoying the moment.

After listening to a couple songs, Tolik reached out and put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Zhon, this is great music. Tomorrow we’ll take you to our concert hall, where we play music.”

I was thrilled at his sincerity and the invitation to visit their music hall the next day. For the first time on the trip, I felt that the possibility that a joint music project was a real possibility and not just a farfetched idea that I’d dreamed up in a small town at the edge of the Pacific Ocean.

Valya looked at my photographs of friends and postcards of Northern California beaches, forests, and a volcano. I felt bad that Tolik couldn’t see them, though he was just as interested as everyone else. He listened to Valya intricately describe the details of each picture, his imagination painting the scenes until he, too, could see the image.

Earlier that evening, Tolik had asked if I wanted to go for a walk and watch the sunset. Valya had gone to the grocery store to get some things for dinner, and he wanted to show me a few sights.

The front door to their apartment building opened onto a large asphalt and grass courtyard where a few cars were parked and a dozen children played. Two grandmothers sat on a bench and watched the children. Large chestnut trees lined both sides of the quiet, dead-end street in front of the building.

“Here comes the bus,” I said, as we waited on a busy street corner several blocks away.

“That is the wrong bus,” Tolik answered. He spoke only Russian. His voice resonated in a deep baritone.

“Kak tee znaesh?” How do you know?

“It sounds different.” The first two buses ran on diesel. When the hum of an electric bus came, Tolik brushed my elbow. “This is our bus.”

We rode the trolley bus toward the city center, winding through neighborhoods on wide boulevards. The ride cost about a nickel. Tolik talked the whole time.

“There is a park over there.” He stared straight ahead but pointed out the other side of the window. “And there is a theater across the street. This is the district where I grew up. As a small boy, I played in that park.”

The bus stopped more than a dozen times. Tolik kept talking and would occasionally reach out to find my arm. I wondered how he could possibly keep track of where we were.

“Here, we get off,” he said abruptly.

“Where are we?” I asked.

“Near the river.”

Tolik held my elbow as we walked quickly along the sidewalk. I’d known few people who walked as fast as I did.

“I like to walk fast,” Tolik said, “This is my exercise, it’s good for health.”

Whenever we came to a curb, he always knew whether to step up or down and which way to turn at each corner, although sometimes he asked the name of the street. While walking back toward their home in the dark, beneath the chestnut trees on his street, I stumbled over a small steel pipe that was fixed across the sidewalk. But Tolik didn’t stumble. He knew the pipe was there. He held my arm to steady me.

“Sorry,” he said, chuckling, and clutching my arm, “I should have told you.”

“Tolik,” I joked, “you are my eyes.”

The next day, I met Tolik and Valya at their apartment. We were joined by Tolik’s sister, Sveta, and her boyfriend, Pasha, who was a musician and a Soviet soldier in the K9 corps. As we walked down the street together to the place Tolik’s band played, we engaged in a rolling conversation full of humor and exclamations. Sveta, who had an infectious, deep laugh, was as energetic as her older brother.

“This is our hall,” Tolik said as we approached a modest, three-story brick building in a residential neighborhood on a tree-lined street.

I soon learned that it was an institute for the blind, not just a music hall.

“Most the people here are blind,” Tolik said.

We entered a large room where about forty people sat at technology benches, assembling electrical circuits. He led me over to one of the benches, where a young man was working and introduced me.

“This is Igor,” he said. “He’s the lead singer and songwriter in our band.”

Igor turned with a wide smile and reached out to shake my hand, greeting me warmly in Russian. We spoke for a few minutes. Then he went back to his work.

Tolik led me through the building, introduced me to the director, took me through a couple more work areas and then to a stolovaya, where he said all the meals were free for the workers at the institute.

We stopped by a small clinic inside the building on the second floor, where people received free medical and dental care. We continued on to a culture hall on the main floor, which contained a stage and theater. That’s where Tolik spent his time.

An enormous image of Lenin hung behind the stage as a backdrop, and the stage itself was equipped with an array of Soviet electric amplifiers and instruments and a PA system. Several of Tolik’s musician friends from the institute were on the stage. A few had normal eyesight and worked in the supply and operations of the building.

Tolik switched on an electric keyboard, someone else flicked on the guitar amps, and the band launched into a practice session for an upcoming music event. I was carried away by the whole environment: the dynamics of the institute, hearing songs from Soviet popular culture, watching the interplay and the band stops, observing the exchange of dialogue to correct some arrangement and then back into the song. It was a familiar ritual.

Later in the afternoon, after the rehearsal session, I sat and played one of the electric guitars, with Tolik on keyboards. I introduced one of my songs, “Journey to the Red Planet.” Igor, who I’d met earlier at his work bench, came into the hall and listened intently. We talked about the song. Tolik and Igor said my Russian translation “needed work” to be a real song. They were being polite.

Tolik and I hummed along on the melody and words. He and Igor asked me to leave my cassette copy of the song for them to work with, and Igor said he would develop a better translation. I was beyond thrilled to be there with two musicians from the USSR who had embraced and shared my imagination. The musical collaboration I had sought had finally taken root in a small theater in downtown Kiev.

Later that evening I came back to Tolik and Valya’s apartment for another dinner. Sveta and Pasha were there, as were a few friends from the institute. After dinner, I took out my melodica, a small wind instrument with a double octave keyboard. I’d carried it with me the entire trip. Tolik became absorbed in a sound that was new to him. When I handed him the small, compact instrument, he ran his fingertips gently over every surface, feeling its shape, then put it to his lips and played as if he’d owned one for years.

One of Tolik’s friends, a poet and a guitarist in his band, picked up a guitar and, with Tolik, wrote and sang a simple verse about our chance meeting.

“We all remain in expectation

In this wonderful September evening

We’ll meet again, Zhon, our dearest one

And we’ll sing all together.”

Before I left their apartment that night, I gave the melodica to Tolik. He was astonished and grateful, and he and Valya both hugged me.

“We want you to have something Russian,” Valya said. “For your home in America.”

“Our Russian samovar,” Tolik pointed toward an ornate electric urn, with a spigot and curved handles. “This is our gift. When you make tea, you will remember us, and this evening.”

Tolik took the samovar off their shelf and presented it to me. Beneath my appreciative gestures and words, I wondered how I would ever be able to carry the thing halfway around the world without smashing it. The tea-making device was as bulky for traveling as a large crock pot, but delicate. I wasn’t accustomed to carrying large appliances on my travels. In an instant, Valya boiled water in the samovar to prove that it worked, then disappeared out of the room, and returned with it packed snugly in its factory shipping container with a convenient rope handle lashed around the box. Now it was twice as big.

When I left their home, everyone accompanied me down the street toward the subway station. The guitarist in Tolik’s band carried the box. We walked in the warm night air and waited for a bus on the corner. I didn’t want to leave this haven of newfound friends, humor, and music. But I was locked into my travel plan. Tomorrow afternoon, I would be on the train back to Moscow.

Tolik insisted that they would all see me off on the train the next day—he, Valya, Sveta, and Pasha. It seemed a grand idea to extend our revelry through to the Kiev train station.

They met me at the hotel, and we took the bus to the station. We arrived an hour before the train’s departure. Already in a great mood, we still had celebrating to do. Tolik pulled a bottle of vodka out of his satchel and said, “Let’s drink to our time together!”

“Yes!”

We stood in a group of five and passed the bottle around, taking sips and bantering away. It was impossible not to be laughing, with Tolik and Sveta always charging the conversations through their energetic outbursts. I told an American joke in Russian that had everybody laughing. Pasha handed me a photograph of him and his K9 German Shepherd at a training ground as a memory. I had a German Shepherd at home, and he and I had talked about our dogs. Valya had brought some Russian rye bread to have with the vodka shots.

It was one of those golden moments, when time is suspended and you are in the moment. The laughter was rooted deep in my chest. After about an hour, we suddenly remembered the train. I think it was Valya who came to her senses first. “The train!” she blurted. I looked at my watch with a sudden sinking feeling.

Everybody grabbed my luggage, and we started to run. We weren’t even near the departure track. We had consumed the bottle of vodka in a corner of the main rail hall. There were probably six different departure tracks outside the station. Sveta and Pasha led the way on the run to the platform. We were a sorry group at that point, moving from revelry to panic in ten seconds flat.

The departure platform was the most distant from the hall. We ran as a group, Tolik holding onto Valya’s arm. When we arrived out of breath, the train was nowhere in sight. It was gone. The reality of its departure sobered us up fast, but as we started looking around the situation became hilarious. We had arrived at the station a full hour early. Everything under control. Then, the vodka, laughter, and chaos.

In the end, I just took a later train to Moscow and got into the city in the late night, just hours before my next rail ticket was scheduled to depart to Belarus and Berlin. There would be little sleep that night, but the memories of the days in Kiev were riveted into my life.