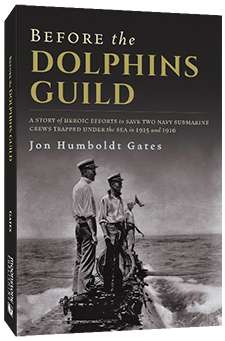

Before the Dolphins Guild

A story of Heroic Efforts to Save Two Navy Submarine Crews Trapped Under the Sea in 1915 and 1916

Introduction

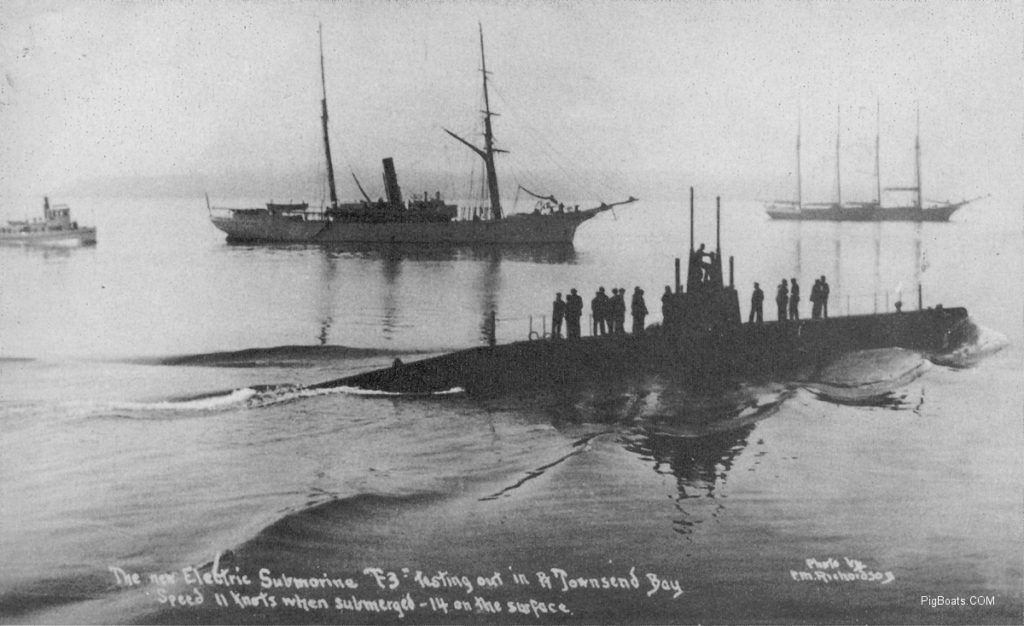

In the early days of submarining, before the Great War, two U.S. submarine disasters riveted the nation as the stories unfolded in local and national newspapers. In Hawaii, the USS F-4 left Honolulu on a routine training run in March 1915 — and disappeared with its crew of 21 men. At Northern California’s Humboldt Bay in December 1916, the USS H-3 crashed onto the sea floor during a treacherous bar crossing attempt and was pinned under roiling surf with its crew of 27.

Both rescue attempts would become historic naval events, requiring tremendous courage, innovation, and stamina from all involved. Jack Agraz, a Mexican-American Navy diver, would dive to record levels in the search for F-4. As a sailor aboard H-3, he would lead rescue efforts from inside the trapped sub. Duane Stewart, an electrician’s mate, would leave behind a harrowing tale of the struggle to stay alive inside H-3. Locals in the towns affected by both wrecks would offer ingenious ideas as well as means of support to the rescuers and stranded sailors.

The experiences of these early pioneer submariners would become the impetus for establishing the US Navy Submarine School in 1917. In 1924, the Dolphins insignia — a submarine flanked by two dolphins — would be introduced as a symbol of achieving true submarine qualification. Crews that apprenticed aboard the F-4 and H-3 subs learned their craft through their experiences and stories, well before the Dolphins guild.

Exploring the Story Behind Before the Dolphins Guild

Watch the Author Discuss the Legendary Submarine Incident with Humboldt Outdoors

Excerpt

F-4

Going Deep

Jack Agraz gave a nod to his crew and slipped beneath the surface of the ocean without a sound. For 22 minutes, he descended without weights, hand under hand, forcing his way straight down the cable. He was going much more slowly this time than on the Friday dives, only two days before. Everyone on the surface felt tension building with each minute. When Jack passed through 50 feet, people on the surface started to lose sight of him in the hazy depths. He became a vague, dark shape and then completely disappeared at 100 feet.

Jack was fighting off the same disorientation he had experienced on Friday. At 150 feet, Jack again couldn’t see very well. He thought he might see better if he took the helmet off. It seemed like a good idea. Narcosis was setting in. It was funny how the depths played with your mind. He slowly removed the heavy brass dive helmet. Now he was 150 feet down without air or head protection. Jack looked around. But as on his prior dive when he tried to wipe down the glass, he couldn’t see any better. His vision was blurred. He was holding his breath for what seemed a very long time, but it was only seconds.

He put the helmet back on. The air pressure from the hand pumps above forced the seawater out of the loose-fitting helmet with a whoosh. The water level dropped in the helmet to around his neck. Jack could breathe again. He took a deep breath through his mouth. The tropical surface air was refreshing.

Then Jack had another idea. He wanted to look straight down into the sea, get a better look at what was below him. The narcosis was building up, clouding his judgment. He gripped the cable and just let his feet float upwards, holding onto his helmet, until he was inverted. His tennis shoes were very light. As he spun around upside down for a better look straight down the cable into the ocean depths, the seawater came rushing back into the helmet. His helmet filled with saltwater again. He held his breath and stared straight down into a green void.

Jack felt relaxed. He wasn’t panicking despite his dive helmet filling with seawater. He changed grip on the wire cable and righted himself. The air pressure again, slowly forcing all the water out of the helmet. The crews on the surface were cranking furiously. Jack knew if he hadn’t been able to get his feet back below him it would have been lights out. But he’d proven to himself that he could work in different positions at that depth and still survive. He thought that might be handy when setting underwater rigging on the sub.

He continued down the cable, hand under hand, feet first, approaching 200 feet again as he’d done on Friday. The surface crew kept uncoiling the air hose as he descended. The air supply team spun the metal wheels as fast as they could. They needed to keep that air flow steady.

The month before, Jack had read in a magazine about a fellow in the Navy on the East Coast who’d gone down 274 feet and felt fine. But that man had worn two pressurized dive suits with an air pocket between them to protect him against the pressure. He also had strapped a small mattress device to his chest and abdomen for protection. The diver practiced for a month before going that deep. He practiced going in and out of a pressure chamber to test the stress of being at that depth. Jack hadn’t had the time to practice. He’d just jumped into the ocean and gone down 200 feet without the slightest idea what would happen. His mind stayed riveted on the F-4 crew below.

Jack wondered what it would feel like to have all that gear. He wore just a light summer jersey. The pressure on his chest was like being crushed by concrete blocks, intensifying by the foot. He willed himself deeper. When he reached 200 feet he looked up toward the surface, which appeared a translucent blue. Occasionally, a fish would swim past and eye him. Some larger fish circled farther above.

He wasn’t blacking out as he had on Friday. As he peered down, the visibility was only about 40 feet, and the water below was dark green and very hazy. He could feel the tug of currents sweeping through the sea at different levels. Jack could not know that the oxygen and nitrogen of the surface air was starting to break down in his body and creep into his consciousness because of pressure at 200 feet.

On the surface, the crowd waited anxiously. Everybody was concentrating on Jack Agraz and F-4 below. As the diver signal line played out and the air hose with it, Ensign Paul Bates called out the depth from the deck of the Navy power launch.

Jack felt confident that day. It was his fifth dive since Friday. He later thought that he could work at 250 feet with this gear. He continued down the cable another 15 feet but hit the end of his tether. He saw the shape of something below him. He gave the signal line a tug. He wanted to go further down.

“He is asking for more line, sir!” Ensign Bates yelled to his commanding officer, Lt. Charles Smith, who was aboard the launch.

“How deep is he?” shouted Smith.

“I make it 215 feet, sir!” Bates responded.

“Holy Moses, man!” Smith barked. “He’s crazy! Don’t give him another inch! Signal him to start up at once!”

Jack felt the sharp tug on the signal line, pulled from the deck, more than 200 feet above him. He knew the commander wanted him back on the surface. He took one last look down toward the sea bottom to confirm what he’d seen, then started slowly going hand over hand up the dredge cable, toward the surface. He knew what he had to tell Lt. Smith.