Night Crossings

Maritime Encounters with Rogue Waves at Night While Crossing California’s Notorious Humboldt Bar

At night, a harbor entrance becomes a dark and unpredictable corridor. One of the most dangerous harbor crossings in North America is the entrance to Humboldt Bay, on the California North Coast. For years, mariners have traded tales of shipwrecks and narrow escapes on the bar. The five stories retold here occurred between 1933 and 1982. They are based on the recollections of sailors who survived the treacherous waters when a rogue wave came out of the darkness. In 1933, two teenagers pilot a small sailboat on a midnight adventure. Forty years later, Christmas Eve turns into a nightmare for the fishermen aboard the Lady Fame. Theirs are two of the voices that evoke the haunting uncertainty of a night crossing.

Bar Stories

In the tradition of oral history, Master Chief Thomas McAdams describes a dramatic night-time rescue mission on the Yaquina River Bar (Newport, Oregon) , on New Year’s Eve in 1953. The video was created by writer and retired Coast Guardsman, Joe Novello, who also wrote a book in 2021 about McAdam’s life at sea – Master Chief Thomas McAdams – The Stories That Made the Legend. During his career in the Coast Guard, McAdams is credited with participating in over 5,000 rescues and saving more than 100 lives. For his actions, he received The Legion of Merit award, USCG Gold Life Saving Medal, the Coast Guard Achievement Medal, and numerous other awards and commendations.

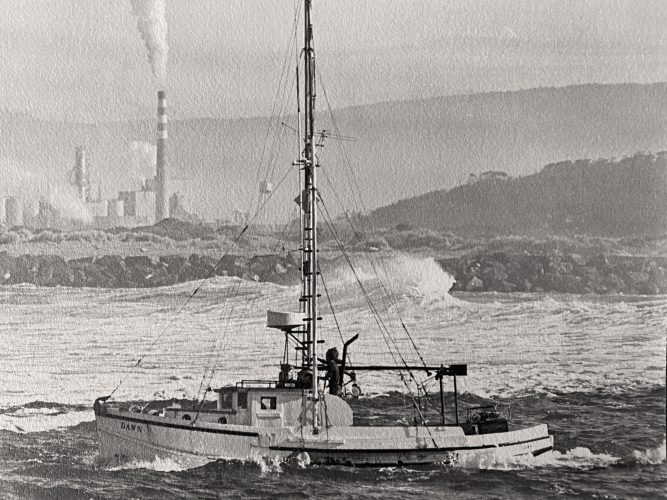

The Humboldt Bar in the daylight

Excerpt

From Lady Fame

Coffee water was boiling. They were only a couple of miles from the bar. Droplets of condensation formed on the inside of Lady Fame’s cold windows and ran down like tears. The pilothouse remained dark except for a soft red glow from the large compass. Floodlights on the Crown-Simpson wharf reflected through the boat’s windows, casting a luminous outline onto Dave’s profile while he watched the wheel. Pete measured a tablespoon of instant coffee into each of the four cups that were lined up on the galley table. Powdered cream and a box of sugar sat near the cups.

Gary had been sitting at the galley table listening to the conversations. He hadn’t said much. This was the first time that he had ever gone to sea. All the images were new to him — going out onto the ocean in the dark, the confinement of a pilothouse, the various marine electronic gadgets, the growl of an engine below his feet, cabin air tinged by the odor of diesel oil, and the foreign jargon of waterfront culture. Gary wondered if he would get seasick.

A couple of days earlier, Steve asked him if he wanted to go for a boat ride on the ocean and take photographs of him and Pete pulling the crab gear. Gary had just finished his fall quarter exams at the college and was off for the Christmas holidays. A trip out onto the ocean sounded like a welcome distraction from school. He needed to relax.

Gary borrowed his father’s snapshot camera for the day, and Steve provided him with an eight-millimeter movie camera to shoot some rolling footage of the crabbing. Steve and Pete had bought the movie camera the previous summer when they had been fighting forest fires for the government in the Klamath National Forest. They had taken some good footage at the fire fronts. But, so far, they hadn’t gotten any action shots aboard Lady Fame. Once the work started, there was never a free hand or a free moment.

Lady Fame glided past the Coast Guard Station in the darkness. The morning began to feel good to Steve. The stars were brilliant. He was looking forward to finishing the day’s work and spending the Christmas holiday with his family. He was happy that Gary had decided to come along. Steve had tried to tell his brother a little of what to expect, but the ocean was a difficult place to describe.

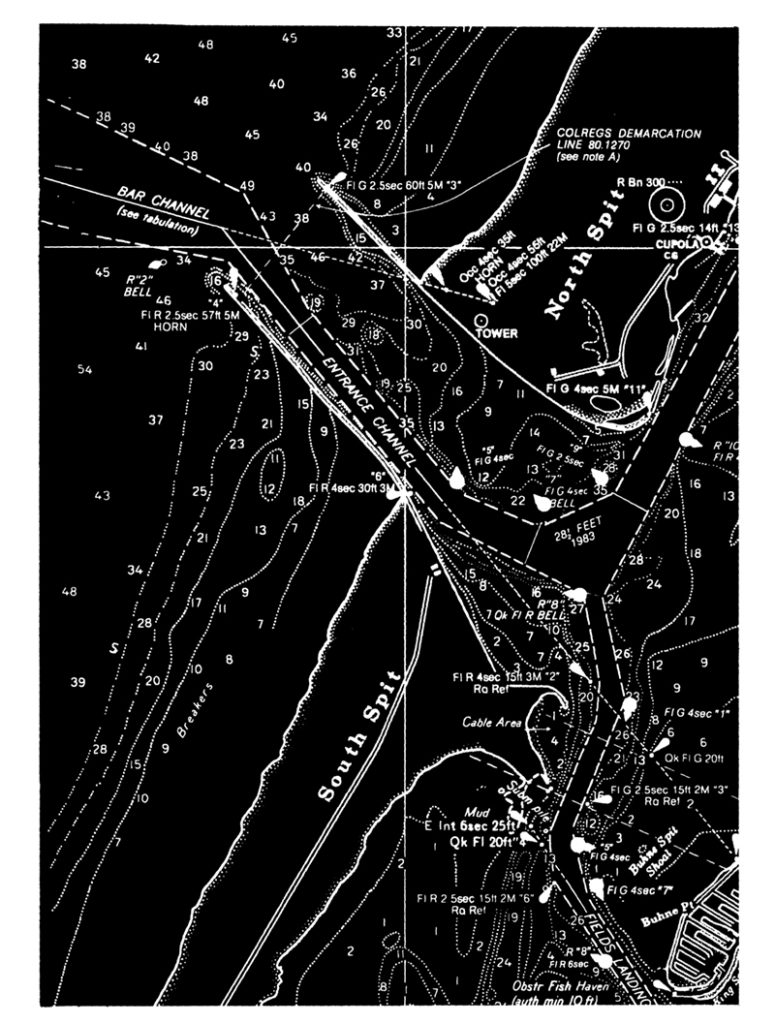

They were nearing the channel entrance. The smooth ride was over. Pete grabbed his coffee cup off the galley table as the boat slowly lifted and rolled to one side. Then he moved forward to the pilot house window on the other side of the wheel from Dave. The boat rose again and dropped. Lady Fame cleared the last rocks of the seawall at the end of the Samoa Penninsula and began to take the swells on its starboard beam. The channel looked dark. Fishermen called this “rock and roll alley.” Everyone held on while the boat tossed from side to side.

Pete saw a flash of white water in the distance out on the bar. It looked like a breaker had closed across the entire entrance. It was hard to tell. He’d only caught a glimpse as a strobe light mounted atop a hundred-foot metal pole on the north jetty flashed once every five seconds.

“Steve,” Pete said, “Did you see that one break out there?” Pete was sure Dave had seen it, but Steve was leaning against the back pilothouse wall looking out the side windows.

“Yeah,” Steve replied. He lifted his eyes a little, but didn’t say anything else. A crescent moon slowly peeked over the east horizon. Steve looked away from the bar.

Dave cranked the wheel hard to starboard when he reached the lighted #7 buoy. They were getting tossed around pretty good. The swells steepened and the Lady Fame’s hull started to pound into them. Dave didn’t like the feel of the seas. He glanced out the port window and saw another buoy farther over.

“Hey! This isn’t the right buoy! That’s it!” he yelled, pointing over at the other buoy. “They put a new buoy in here!”

Lady Fame was headed for a shallow sandbar in the middle of the harbor entrance. Pete could see white water on its shoals. Dave cursed and fumed. He spun the wheel hard to port and turned side ways in the steep swells. The boat rolled heavily. Loose objects started flying off the shelves. Pete grabbed a sliding coffee cup before it hit the deck and stuffed it into the sink along with an ashtray, a couple of Kurt Vonnegut books, and the coffee fixings. Gary braced himself against the wall with his legs.

“Damn it! I told you guys to secure that stuff a hundred times,” Dave exclaimed. “You can’t leave things lying around like in a house. Keep it all ship shape!” Dave was holding all the junk down on the dash with the hand that wasn’t on the wheel. His lunchbox slid with a crash from where he had left it on the galley table.

Pete held onto the table for balance as he moved around and secured the flying debris. He wedged himself back in alongside the wheel. Dave was upset about the buoy. It was a brand new one. The Coast Guard must have put it in the day before.

Several minutes later, Lady Fame rounded the real #7 buoy and left the steep broadside swells of “rock and roll alley” behind. Against the dark sea, the brilliant flash of the strobe illuminated more white water in the middle grounds. Dave grabbed a radio broadcast mike.

“You got this thing on there, Ray? Come back.”

Another crab boat was about a quarter mile behind the Lady Fame. Dave knew the skipper. After a moment of static, Ray answered.

“Yeah, Dave.”

“Yeah, Ray, they got an extra buoy here. Looks just like #7, but it’s too far north. Leads you right into the middle if you turn at it, okay?”

“Right, Dave. Saw your turn there. We’ll be watching for it. We’re getting slopped around quite a bit back here. Only another forty-five minutes ‘til we get some light here. I think we’ll wait. You call back when you get outside, okay?”

“Fine, Ray, fine. We’ll go out and take a look at it. Give you a call when we get outside. Okay, I’m clear,” Dave closed. The boat was riding smoother now.

“Appreciate it, Dave. We’d appreciate it. You take a look … we don’t have all the gear out there that you do. We can afford to wait for a little sun. Okay.”

Steve remembered “rock and roll alley” well from the opening day of the previous season. The boat in front of theirs had rolled off a steep swell and lost forty crab pots off its rear deck. It was a real madhouse that morning in the dark. Steve was pulling crabs for the first time. His skipper had never run his own boat before and hadn’t taken care of several last minute things. The squid used for bait was still frozen in its box. Preparing the bait was supposed to have been Steve’s job.

The skipper’s black Labrador retriever had run up and down the deck barking at a harbor seal, then suddenly jumped overboard. The dog blended into the dark morning water like licorice in ink. After a ten-minute search with a spotlight, they finally dragged the dog back aboard.

When daylight broke, the jaws of the jetty were frothing everywhere but the channel. Even the steep swells on the channel had white foam dancing on their tops. A flotilla of boats jammed the harbor entrance. No one was going over the bar. But it was opening day, and the crab fishermen were hungry. Most of them slipped over the bar anyway. They took a real slamming. Steve had spent the morning chasing a block of frozen squid around the deck with a big machete. They hastily laid their pots that day as close to shore as possible, then dashed back in and considered themselves lucky for making it.

Crossing out over the bar on a rough day bore an odd resemblance to entering a crab pot. The crabs would smell fresh bait oozing from the trap and, like fishing boats milling about the entrance, would walk around the pot until they located the narrow tunnel opening in its side. Thick stainless steel wires hung like bars at the end of the crabpot tunnel. They swung in one direction only. Once the crabs had passed this point, they would fall to the bottom of the cage and be trapped. If the bar started breaking across the entrance channel, a boat in the open sea would be trapped. Fishermen had to be careful. The ocean didn’t have a size limit. It took whatever it could get.

Steve watched another breaker close across the middle grounds of the bar. The white water flashed into view under the north jetty’s strobe and then immediately dissolved into blackness. The sudden brilliance left spots in front of his eyes and obscured the natural lighting. The strobe fired again and again like a photographer’s flash bulb in a dark alley. Lady Fame rose on the big swells and sank into the troughs. Steve’s night vision was bordering on fantasy.

The strobe pulsed. Steve caught a glimpse of a breaker closing the whole north side of the entrance, smashing onto the rocks of the north jetty. Five seconds later, the foamy aftermath froze in a momentary swirl of black and white. Lady Fame took another sharp dive. The rectangular starboard window that Steve looked through could have been a malfunctioning television set with no vertical hold and an intermittent picture. The night crossing was being edited into stop action footage with five second voids. No color, only the subtlest white and black tonal gradations. Steve leaned against the rear pilothouse wall, next to the warm oil stove, and stared out the window at the pulsing scenario. The constant growl of the diesel was relaxing to him. Another large swell rolled toward the boat. Lady Fame started to climb.

* * *

Pete and Steve had stood together on the summits of half a dozen West Coast volcanoes. The ascents of such massive prominences had brought them together — like two war veterans. But they had never been so deeply challenged as the time they had climbed Mt. Whitney.

Before them, a long, narrow rock ledge traversed a smooth granite face. Below the ledge was a 1,600-foot drop into boulders. Pete and Steve had to cross the ledge to reach the summit.

The ledge was about a foot wide with a slight downward slope. The wall offered no handholds. Both climbers put their palms to the wall. The rock felt cool and solid. They took deep breaths to relax and focus their concentration as they stepped from the familiar into the unknown. One step at a time. Moving sideways. Faces to stone. Until they reached the other side. Safely.

* * *

“Who’s steaming up my windows?” Dave sounded annoyed. “Oh … sorry, Dave,” Pete answered, turning to look back at the stove. “The coffee water is boiling again, I guess.”

“Hell, I can hardly see.” Dave reached up and wiped the moisture off the window with his hand. The end of the south jetty was just off the port bow.

Steve grabbed a roll of towels and threw them forward to Pete. He tore off a handful and stretched in front of the wheel to clean the smudged glass.

“Excuse me, Dave.” The dashboard dug into Pete’s stomach as the boat lurched and hit the bottom of a trough. Lady Fame creaked as she started up another steep one.

“Thank you, Peter.” Dave was pleased he could see again.

Just outside the end of the south jetty, the seas began to lose some of their sharpness. The steep plunging dives became a little less accented, but the swells remained about fifteen to twenty feet high.

Pete could see the dim shape of the bell buoy surging up and down off the port side. It tugged at its mooring chain with a frantic motion. He looked back at Steve and Gary. Steve just nodded, he wasn’t smiling much. He looked relaxed. So did Gary. Pete had been nervous going over the bar. First, the new buoy had led them into the sand shoals, then all those breakers had appeared off their starboard side. Some of the seas had threatened to break in the main channel. The crossing had been one of the roughest Pete could remember. He was glad they were on the outside now. He lit a cigarette.

Pete stared out the large pilothouse windows, but it was still too dark to see the swells until they were right in front of them. A big roller slid under the boat and lifted it as high as a two-story house. Pete grabbed the dash as Lady Fame tobogganed down the backside. “Well, boys,” Dave said breaking the silence. “I think it’s a little too nasty to work on it today. There’ll be better days than this. I think well go on out to the sea buoy and wait for the dawn to lighten things up. I’ll call Ray and tell him to go home and go to bed. Nobody’s gonna be fishing the crabs today.”

“Yeah … it’s pretty rough,” Pete said. He was glad that they were going back in. They’d be back to the dock by eight o’clock. He thought he might do some last minute Christmas shopping when the stores opened.

“Pete, see if you can spot the sea buoy. Keep your eye on it when you do.” Dave backed off the throttle a little. They were rising up the face of another big one. If he didn’t back off a little, everyone’s head would bounce off the ceiling when the boat dropped off the swell’s backside. At the top of the wave, Pete saw the sea buoy’s white flashing light. It wasn’t far away.

“There it is, Dave.” He pointed. Dave nodded. He’d seen it too. They dropped into another trough. Pete lost sight of the buoy.

The swells were getting bigger. He felt a rush of nervousness. He put out his cigarette and grabbed a paper towel to clean the windows again. They were rising fast on this one. Pete grabbed the dash. White water tumbled out of the darkness and splashed across the windows. Spray covered the pilothouse.

Jesus! Pete thought. They came down hard off the backside. Lady Fame veered slightly askew.

Pete’s mind was racing. God damn, that one had foam on top! He’d never seen one like that. Not even on the bar. They were almost out to the sea buoy. Right there in front of us! Jesus! Where did that wave come from? It looked like it was gonna break! Pete looked over at Dave who was concentrating on the wheel. He gave a little more throttle to the boat and it started to straighten.

“Hey, hey,” Pete said anxiously, turning to face Gary and Steve. “Now that was something, eh? First time we’ve ever taken white water on the windows of this boat.” Pete turned back to the window to look for the sea buoy. He couldn’t see it.

Dave chuckled quietly. Steve half smiled but watched the forward windows intently. He removed the hot water pot from the fenced-in stovetop. The compass light’s red glow made everything seem distant. Condensation dripped like beads of sweat from the pilothouse windows. Pete grabbed the towels again and started to wipe the glass, but then stopped. A moment of silence passed. Everyone focused at once and looked out the windows to the northwest. It was as if the diesel and the sound of the ocean had disappeared. Not a word was spoken.

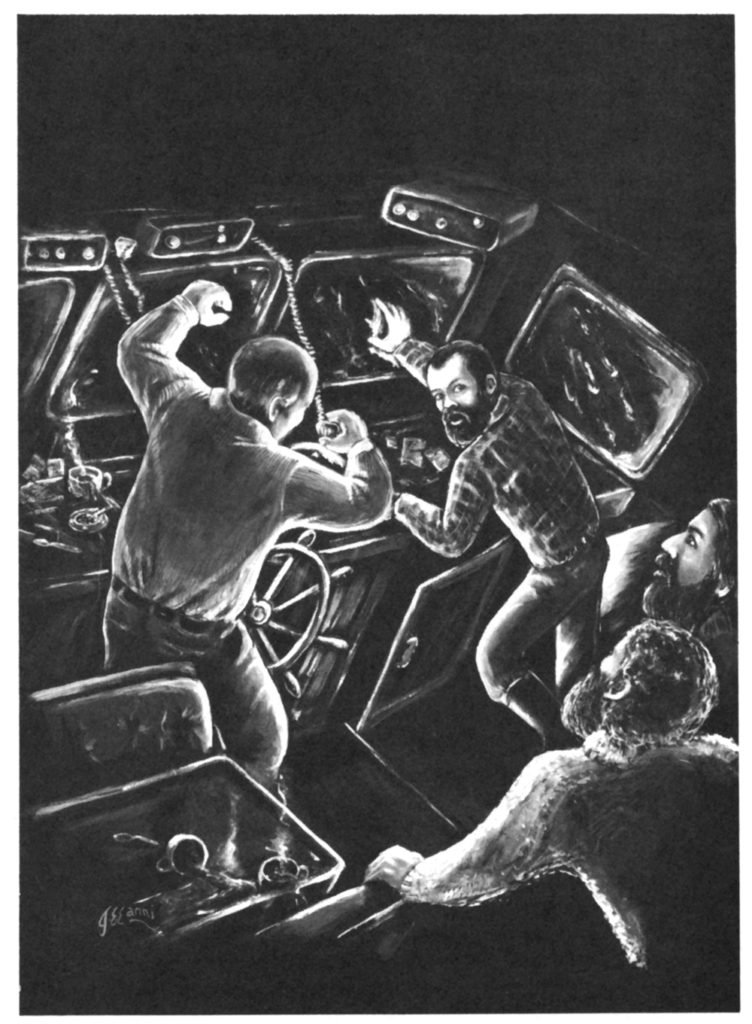

They couldn’t really see the wave, only the white water. It was cresting into a breaker at about thirty feet, and toppling over. A deep rumbling pulsed through the boat. Steve felt a chill run down his neck. Lady Fame started to rise.

Dave Rankin reached for the broadcast mike. In a mastery of understatement, he said casually, “This one’s gonna hit us hard.”

The giant wave snatched up Lady Fame like a twenty-dollar bill on a street comer. Everyone grabbed for something solid. Stomachs hollowed. The bow pointed to the stars. They were rising, rising! Fast! The force pinned Steve against the rear wall. Dave fell to the floor. He pulled the radio broadcast mike with him. The windows suddenly turned white. Pete couldn’t hold onto the dash. Too much pressure. He tumbled to the floor. There was a tremendous impact of water.